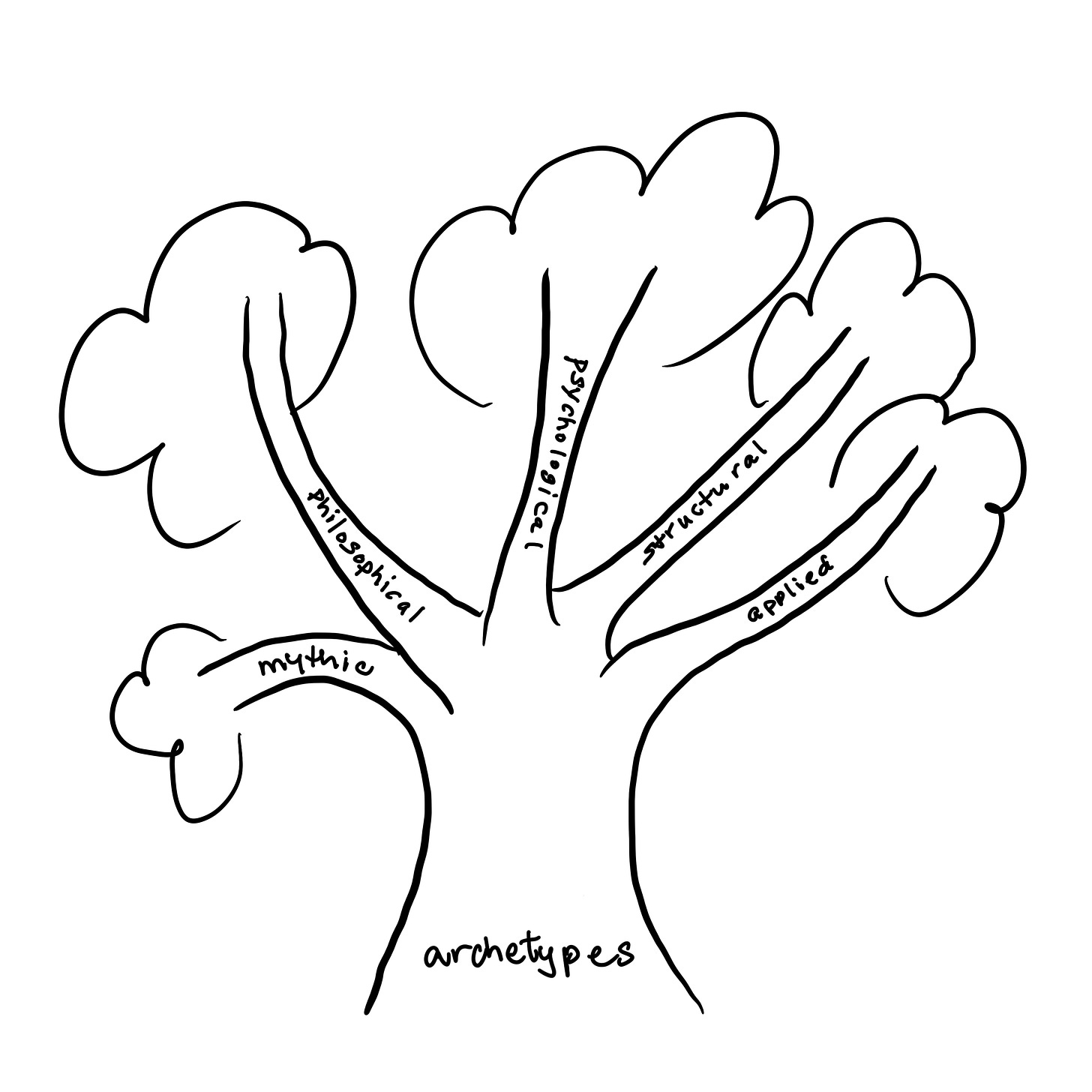

Archetypes—a Lineage

Archetype did not begin with Jung.

Nor did it begin in psychology.

The word itself predates modern theory. Archē is Greek for “beginning” or “origin,” and typos means “imprint” or “pattern.” Long before archetype became a psychological term, it pointed toward something structural—an originating form.

Plato circled this idea in his theory of Forms: immutable, underlying essences from which particular instances derive. In this philosophical lineage, archetype suggests a pattern that precedes manifestation—something more real than its expressions.

Mythic traditions offer another branch. Across cultures, we find recurring figures: the Hero, the Great Mother, the Trickster, the descent into the underworld, the dying-and-rising god. These patterns were not originally called “archetypes,” yet they repeat with striking familiarity. Here, archetypes emerge through story—recognizable symbolic forms that surface wherever humans narrate existence.

In the twentieth century, Carl Jung introduced archetypes into psychology. He proposed that these recurring figures were not only cultural but psychic—structural elements of the collective unconscious manifesting in dreams, art, and religion. Archetype moved inward. Myth became internal.

If Jung moved archetype inward into the psyche, Propp and Lévi-Strauss moved it outward into structure.

Propp analyzed folktales by function, identifying recurring roles such as donor, helper, and villain rather than their symbolic meaning. In essence, he charted the “logic of adventure” and revealed the skeleton of a narrative.

In contrast, Lévi-Strauss offered a different perspective, proposing structural oppositions that generate tension within myth. He argued that these oppositions reflect deep patterns within human cognition.

Consequently, archetypes become less about symbolism and more about underlying pattern organization, functioning closer to grammar than to mythology itself. This marks a shift from symbolic content to structural logic.

Across these branches—philosophical, mythic, psychological, structural—one idea persists: recurrence structured into form.

Patterns exist in reality independent of recognition. But archetypes do not. Archetypes emerge when cognition stabilizes recurring human conditions into transmissible symbolic forms. They are not metaphysical blueprints nor psychic fossils. They are compressed recognitions—the mind’s way of remembering what it repeatedly encounters.

If earlier archetypal theories sought universal structures, contemporary applications often seek functional clarity.

In contemporary contexts, archetypes often function less as inherited truths and more as applied tools. Brands use them. Personality systems use them. Creative frameworks use them. These models are heuristic tools—categories for recognizing recurrence.

AuthorKind Archetypes belong to this contemporary branch. They are not Jungian psychology, nor narrative mechanics, nor metaphysical claims. They are observed creative energy configurations: gathering, incubating, shaping, articulating, offering, guarding.

Incubation is inward containment and consolidation. Articulating is the energy of precision and translation. Guarding is boundary and preservation.

AuthorKind Archetypes describe energies and postures—creative states.

Their function is navigational rather than definitional. They help identify how energy is currently moving—and whether that movement feels aligned or distorted.

If archetypes are stabilized cognitive recognitions of recurring conditions, then their value lies not in antiquity but in application. They become mirrors. They reveal posture.

The question, then, is not which archetype one permanently is.

The question is whether one has lingered too long in a particular creative stance—and why.

Are we gathering to avoid offering?

Guarding to avoid risk?

Forcing articulation before incubation has matured?

If archetypes help us notice these patterns without shame, they serve a useful purpose.

Perhaps archetypes do not precede us.

But they do reveal what we repeatedly encounter.

And what we choose to do with that recognition remains ours.

I thought Lévi-Strauss just made jeans. Who Knew?

And I think the archetypes can help us validate, too. If we recognize that we've been gathering for a long time, we can take a look and see if that's what our current project needs. Maybe so! And then we don't have to feel bad about continuing in that state. Or recognizing what condition needs to be met to transition to another state. It's such a useful framework, something I think can help focus and guide creative effort.