Fibonacci Poetry

blue

bird

above

rushes home

to feed the nesters

daddy blue always true to fate*

*my first attempt at ‘Fibbing.’

Patterns often announce themselves before we name them.

The short poem above follows one such pattern. It’s a Fib: a Fibonacci-based poetic form that builds line by line. Its relatively recent naming, however, tells only part of a much larger story.

The Fib, as Generally Taught

A Fib is typically defined as a poem whose line lengths follow the Fibonacci sequence, with each line containing a specified number of syllables—most commonly:

1 / 1 / 2 / 3 / 5 / 8

This definition is associated with Greg Pincus and has been widely repeated in craft essays, classrooms, and online journals since 2006.

That definition is accurate—but incomplete.

The Longer History of the Pattern

The Fibonacci sequence is named after the Italian mathematician Leonardo of Pisa, better known as Fibonacci (“son of Bonacci”), who introduced the pattern to Western European mathematics in Liber Abaci (1202).

However, Fibonacci did not discover the sequence. As early as 200 BCE, the Indian poet-mathematician Acharya Pingala studied Sanskrit poetic meters and described syllabic patterns that align with what we now recognize as Fibonacci logic.

In other words, poetry was already counting long before the sequence acquired its modern name.

The Pattern Itself

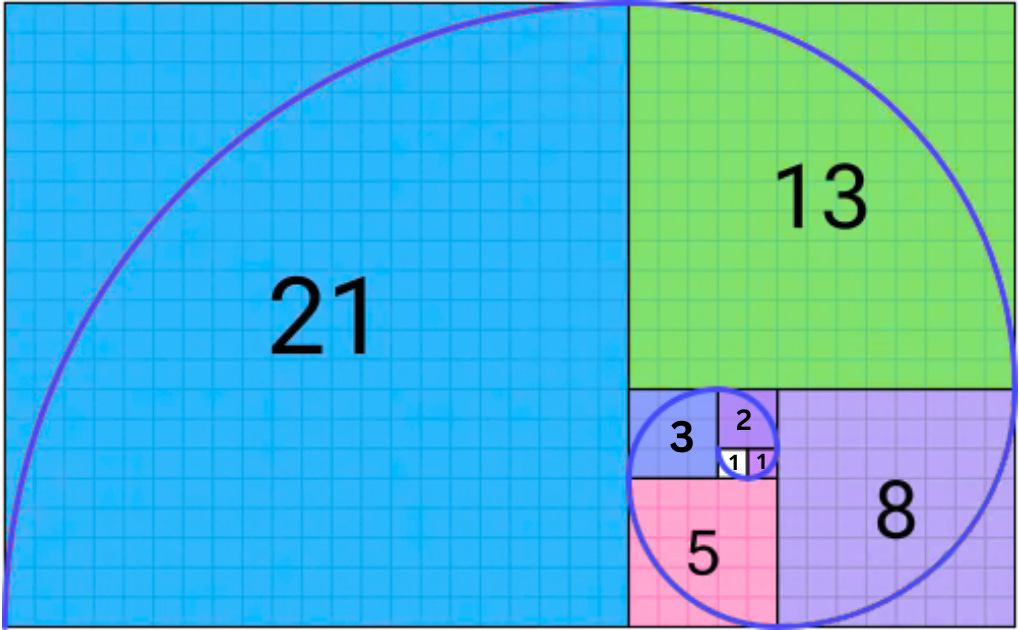

Regardless of who first recognized it, the Fibonacci sequence has come to represent a recurring pattern of balanced growth—each number the sum of the two that precede it:

0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21…

We see this pattern echoed widely:

In nature: sunflower seed arrangements, pinecone scales, nautilus shells, hurricanes, galaxies

In visual art and architecture: the Mona Lisa, the Vitruvian Man, Hokusai’s Great Wave, the Parthenon

In poetry: Sanskrit chandas, syllabic verse, and—more recently—the Fib

The impulse is the same: number as a quiet shaping force.

Number and Poetry

Poetry has always been numeric, whether poets foreground that fact or not. Prosody—the patterned use of rhythm and sound—long predates modern experimentation.

Across cultures, poets have relied on constraint:

Sanskrit prosody employed syllabic patterning

Greek lyric meters were mathematical and recursive

Japanese forms such as tanka and haiku normalized fixed syllable counts

Medieval pattern poems (carmen figuratum) used numerical architecture

20th-century experimental poetry (Oulipo, concrete poetry) embraced math, recursion, and rule-based composition

Seen this way, number-driven poetry is not the exception. It is the rule.

What George Pincus Did—and Why It Matters

So no—George Pincus did not invent Fibonacci poetry, nor did he invent the impulse to let number shape verse.

What he did do, on April 1, 2006, was crucial.

In a blog post—originally framed as a kind of April Fool’s gesture—Pincus defined a short, repeatable poetic form, named it the Fib, and released it into a networked literary culture ready to receive it.

That act of naming mattered.

Forms do not become forms until someone says:

This is a thing. Here are its bones. Try it.

Because of that moment, the Fib became teachable, shareable, and repeatable. And because of that, it has endured.

An Invitation

In April 2026, the Fib will mark twenty years of formal existence as a named poetic form. By a happy coincidence, that date also marks my own first anniversary on Substack.

I intend to honor both.

I invite you to write a Fib and share it with me so that I can post a collective celebration on April 1, 2026. I’ll be contributing one myself—an ebb-and-flow variation that plays with accumulation and release.

If you’re curious, playful, or simply fond of patterns, I hope you’ll join me.

Save the date: April 1, 2026.

here.

now.

this is

the only place

where you can safely stand.

The rest belongs to Maya, queen of illusion.

Very cool. I know the Fibonacci sequence but had never heard of applying it to poetry/text.