Whale's Song - Part 1

Life IS Communication

The whales do not sing because they have an answer, they sing because they have a song.

~ Gregory Colbert, an “apprentice to nature”

Part 1: Life is Communication

In the Intro, we gave you an overview of where we are headed in the Whale’s Song series. Here, in Part 1, we dabble in a concept too often taken for granted—communication.

Life, at its most fundamental level, is not just about survival; it is about communication. Without it, survival diminishes and life fades.

But what exactly is communication? Who does it, and why?

Every living thing transfers information—sending signals, whether through sound, movement, chemicals, or vibrations.

The whisper of wind through a forest, the deep pulses of a whale’s song, the silent warning exchanged through fungal networks underground. Some signals we recognize. Others remain invisible to us.

Essentially, communication is the transfer of information.

Different disciplines define it in different ways, but at its core—whether through speech, smiles, or birdsong—it all boils down to exchanging meaning.

And what is storytelling, if not the art of transferring information from one mind to another?

Sounds—Social or Sensory

Living beings communicate because their survival depends on it. Some sounds are meant for others to hear. Others are simply ways of perceiving the world.

Sensory sounds (used to gather information):

Echolocation (dolphins, bats)

Sniffing (dogs, elephants)

Body-generated signals (rattlesnakes shaking, fish using lateral lines to detect motion)

Social sounds (used to convey messages):

Humans: speech, laughter, crying, whistling, humming, singing

Marine mammals: whale songs, dolphin clicks, beluga whistles

Land mammals: howls (wolves), roars (lions), purring (cats), drumming (kangaroos)

Birds: calls, mimicry, melodic songs

Insects & Others: wing vibrations (bees), foot-stamping (elephants), ultrasonic signals (bats)

Survival? Yes. Social bonding? Yes. Are you free for dinner? Maybe.

Would you consider an orca giving a TED talk? Let us know after you watch this.

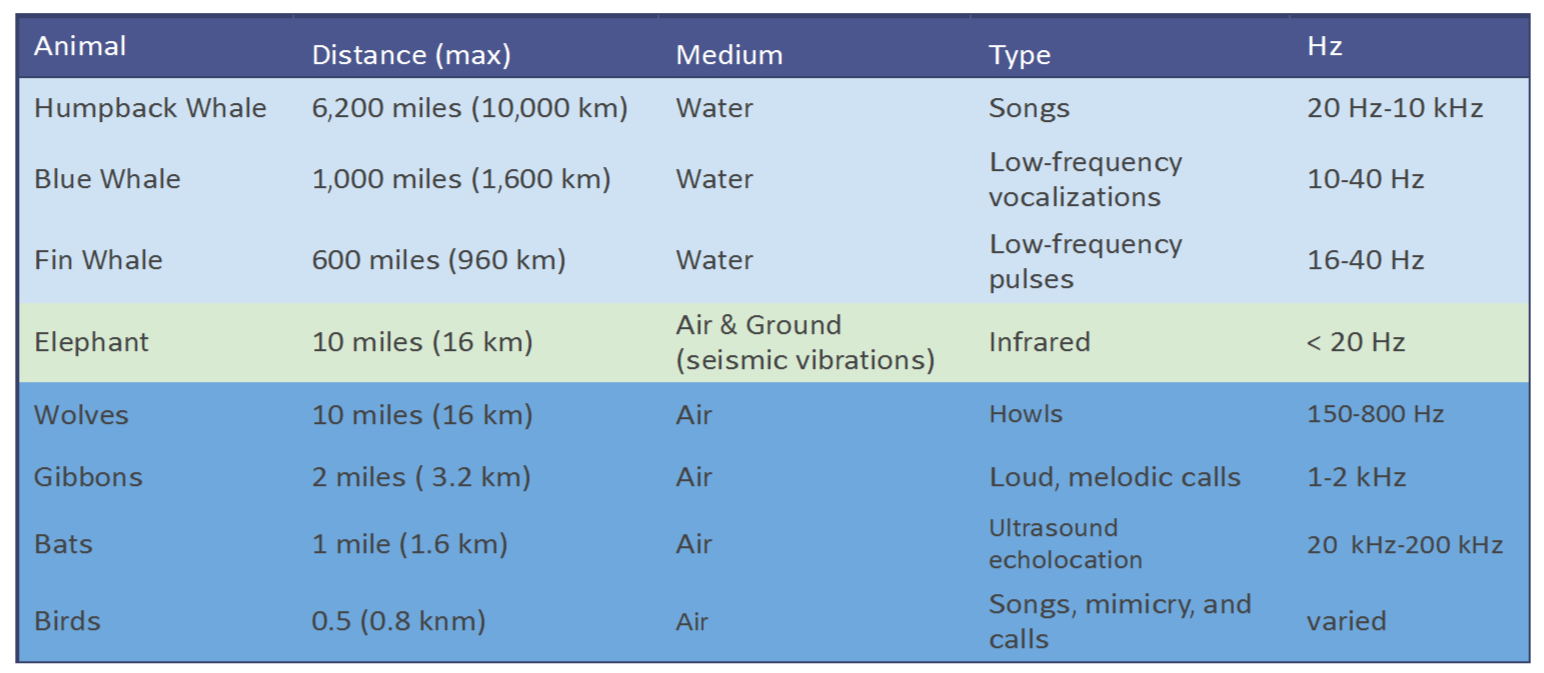

Long-Distance Relationships

Across the animal kingdom, communication isn’t just about what is said—it’s about how far a message can go. In vast oceans, dense forests, and open savannas, reaching others is just as crucial as speaking.

With oceans covering 71% of Earth's surface, it’s no surprise that the longest-distance calls belong to marine life.

Sound travels four times faster in water than in air, allowing whales to hold conversations across entire ocean basins.

And how about space? We know it doesn’t conduct traditional sound waves the way water and air do—it’s a vacuum. But let’s not rule out communication in space yet...

Imagine standing at the edge of an ocean, feeling the low, reverberating hum of a whale’s call vibrating through the waves. The sound is ancient, intelligent—yet still largely undeciphered.

What is it saying? Is it saying? Of course it is.

Now, cast your gaze upward. If life exists beyond Earth—of course it does—it too must communicate. But will we recognize its language when we hear it?

If whales can sing across oceans, and elephants can feel seismic signals through the ground, what undiscovered forces might carry alien messages across the vast emptiness of space?

Perhaps space isn’t silent at all—we just haven’t learned how to listen.

Beyond Animals: Non-Vocal Communication

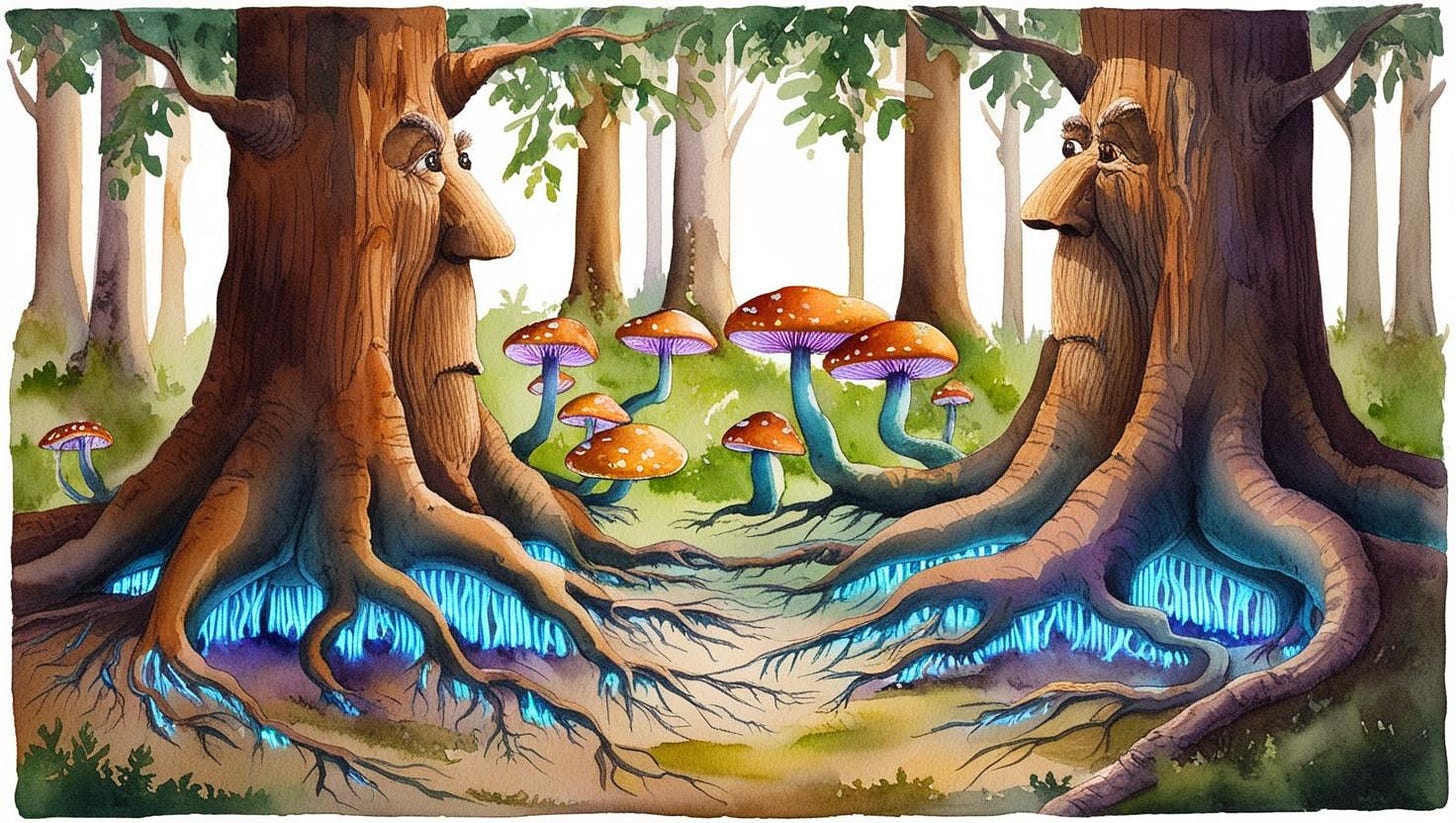

Beneath our feet, forests engage in whispered conversations through an invisible network—the Wood Wide Web—a term coined to describe how mycorrhizal fungi connect trees in forest ecosystems.

This system is part of a broader mycelial network found wherever fungi grow—even in soil without trees.

Image created by JL Tooker @ Canva Dream Lab

Not just for kids → A Closer Look at How Trees Talk to each other.

The mycelial network is a massive cooperative system of tiny thread-like filaments called hyphae, which fungi maneuver to share nutrients, send distress signals, and even 'warn' their neighbors of impending threats.

Meanwhile, bacteria coordinate their movements through quorum sensing, releasing chemical signals to synchronize their actions—an invisible language shaping entire microbial communities.

I think the easiest application to help people understand what quorum sensing is and why it's important to study is to tell them that if we could make the bacteria either deaf or mute, we could create new antibiotics.

If forests can whisper through roots and fungi can send chemical warnings, why should extraterrestrials need words at all?

Which models might best prepare us for making first contact?

The way we define communication—through words, speech, and gestures—may be narrower than we think.

If plants, fungi, whales, and even microbes exchange complex information without needing a spoken language, why do we assume that extraterrestrial beings would communicate in ways we easily recognize?

Could it be that alien messages have already arrived, but we simply don’t have the ears to hear them?

NOTE: Resources & Readings for The Whale’s Song can be found here.

Coming Next

In Part 2 of Whale's Song, we’ll examine why human bias may be stifling our ability to communicate across species—and beyond.

Take this fun quiz to get you prepared for next time:

So, next week, let’s step beyond the limits of human language and see what we’ve been missing.