Whale's Song - Part 2

Linguistic Models for Extraterrestrial Communications

Part 2: Linguistic Models for Extraterrestrial Communications

In Part 1, we set the stage for developing extraterrestrial communication by looking at the basics of communication, language and conversation. Here, in Part 2, we dive deeper into linguistic models and which might serve best to prepare for ‘first contact.’

Is Our Bias for Human Linguistic Models Preventing Us From Speaking to Non-Humans?

Right now, scientists are attempting two-way conversations with whales. AI is analyzing their songs. Algorithms are decoding bat vocalizations. And tomato plants are asking for water or conversing via AI. (sorta).

What if the first alien message has already been sent—but we’re just too human to recognize it?

In this installment, we explore linguistic models that could forge a path toward understanding extraterrestrial communication. But first, let’s take a step back. Are our language assumptions blinding us to non-human messages?

Communication, Language, and Conversation

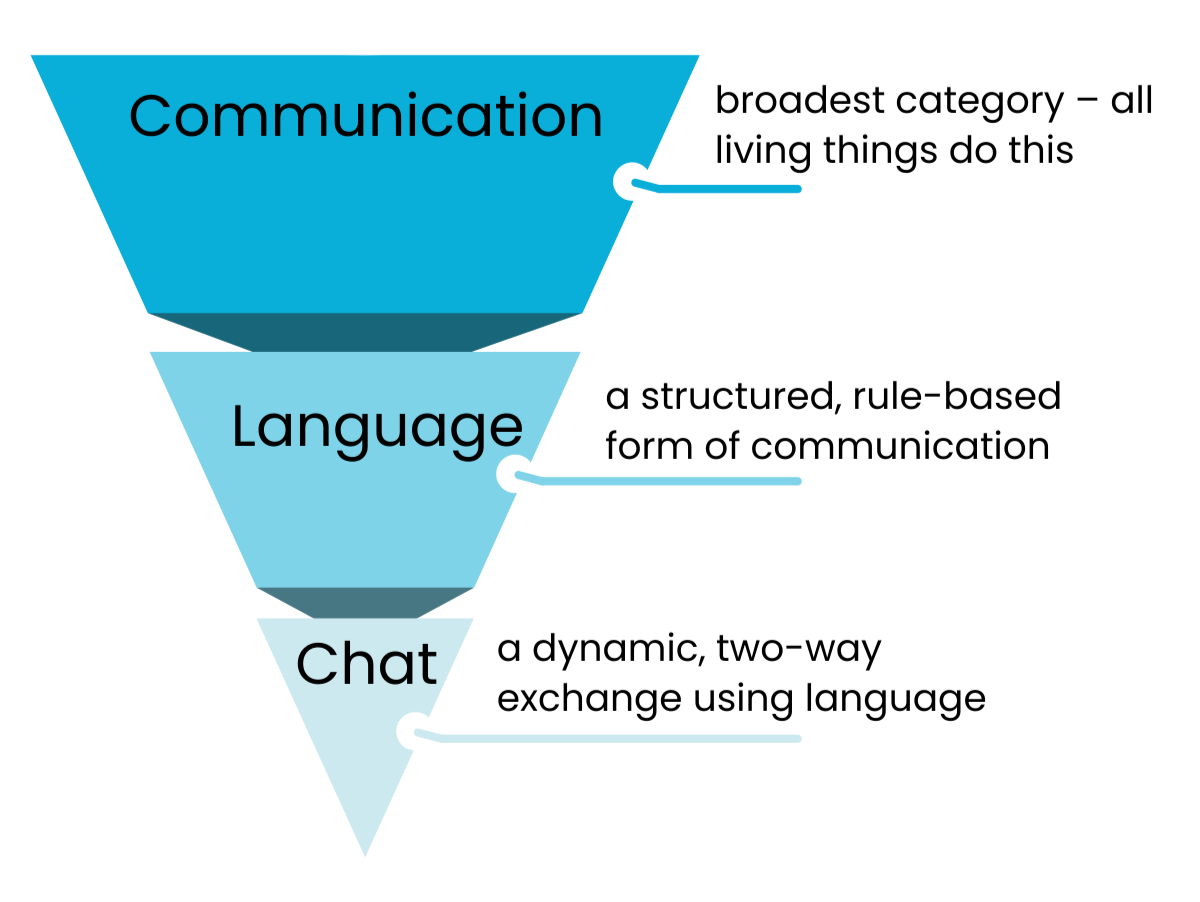

Before we tackle alien communication, let’s define the three essential layers that shape how we understand information exchange—as humans.

Communication: The Broadest Concept

The transmission of information between entities.

Can be intentional or unintentional (e.g., body language, scent trails, electromagnetic pulses).

Does not require words, structure, or intelligence.

Examples:

A human sighs in frustration, and others interpret it as stress.

A plant releases chemicals to warn neighboring trees of danger.

A wolf’s howl signals its location to a distant pack member.

Is this signal a conversation or just a broadcast? (Hint: The answer might surprise you!)

Bottom Line: Communication is everywhere—even single-celled organisms exchange chemical signals.

Language: A Structured Form of Communication

A system of symbols, sounds, or gestures used to transmit complex meaning.

Requires rules, structure, and shared understanding to function.

Can be spoken, written, gestural, or even biochemical (e.g., quorum sensing in bacteria).

Examples of Non-Human Language-like Systems:

Dolphin signature whistles (each dolphin has a unique "name" call).

Whale songs (patterns that evolve over time and spread across populations).

Mathematics & computer code (rule-based symbolic systems).

Bottom Line: Language is a subset of communication, but not all communication is language.

Want to hear a Dolphin ‘conversation’?

Conversation: A Two-Way Exchange of Language

A socially-driven, interactive process where participants take turns exchanging meaning.

Typically spontaneous, dynamic, and context-driven.

Examples:

Two humans talking in person or via text.

A dolphin mimicking another dolphin’s whistle in response.

A parrot learning and responding to human words.

Bottom Line: Not all language use is conversational. A book uses language but doesn’t have a conversation.

Key Takeaways & Writer Considerations

All conversations involve language, but not all language is conversational.

All language is communication, but not all communication is language.

Some animals communicate without language (bees, ants, fireflies).

Some species (whales, dolphins) may have “language-like” structures but lack structured conversation.

Humans may be unique in having true “conversations”—but we are still investigating whether whales, dolphins, or other intelligent species do too!

Did you take the Linguistics Bias test included in last week’s post? How’d you do? Score doesn’t matter … learning does. If you missed Part 1 of the series and you’d like to take this fun quiz, go for it.

The Human Bias: Speech-Centric Thinking

Where did we get the idea that language must resemble human speech to be considered “real” language?

Better yet—how did we let human language shape our assumptions about what counts as true communication?

While scientific disciplines may define communication in slightly different ways, we can agree on this:

Communication is the transmission of information.

It does not require words, structure, or even intelligence.

Language is one form of communication—but not the only form.

And yet…

When humpback whales like Twain engage in call-and-response interactions, we hesitate to call it “conversation.” Yet we quickly refer to ‘whale song’—not a conversation. Why? Because it doesn’t look like human speech?

Maybe we’re asking the wrong question. Instead of debating whether song qualifies as language, what if language is just one small part of something bigger?

Maybe song is the vessel, and language is just a passenger.

Not a prediction, just a description—thank you, Ursula K. Le Guin.

What if our own understanding of communication is limited—not because other species lack language, but because we’ve been listening for the wrong thing?

How Have Human Language Models Been Used to Communicate with Non-Humans?

To crack the code of non-human—and potentially extraterrestrial—communication, we must step beyond human assumptions.

Scientists have tested three primary models to bridge the gap with non-human species … and possibly a fourth overlooked one. Each offers insights—and limitations—into how intelligence might communicate beyond our world.

Four Models to Bridge the Communication Gap

1. Symbolic Language: Teaching Meaning Through Signs

Bonobos & Lexigrams → Kanzi, a bonobo, learned to press visual symbols on a keyboard to form ideas.

Alex the Parrot → Not only mimicked words but understood them, answering logical questions.

Dolphin Studies → Dolphins comprehended artificial gestural languages, showing syntax understanding.

2. Mathematical & Logical Models: Seeking Universal Patterns

Arecibo Message (1974): A binary radio signal containing numbers, atomic structures, and human figures was beamed into space.

SETI’s Whale-SETI Project: Scientists are sending structured sound sequences to whales to see if they can recognize patterns.

3. AI & Machine Learning: Decoding Languages Beyond Human Perception

Project CETI: Uses AI to decode sperm whale clicks, treating language as data rather than speech.

Bat & Elephant Vocalization Studies: AI has detected individual "voices" and social interactions in previously misunderstood species.

4. Body Language & Gesture-Based Communication: A Missing Model?

While mainstream linguistic theory prioritizes spoken and structured symbolic systems, many species rely on gesture, movement, and visual cues to convey meaning.

Could this be a missing model in our search for extraterrestrial communication?

Consider:

Koko the Gorilla signing complex thoughts.

Octopuses shifting color to signal emotion or intent.

Bees dancing to share navigational data.

If non-human species already communicate through physical expression rather than words, could an extraterrestrial species do the same?

Perhaps our first conversation with extraterrestrials won’t be words at all—but patterns, movement, and sound. And if our current models aren’t enough to decode the unknown, shouldn’t we be open to expanding them?

The Takeaway for First Contact

If humans ever encounter an alien species, we may need to rethink what language is. Instead of words, our best tools might be:

Symbol-Based Lexicons (Pictorial or gestural systems)

Mathematical & Sound Sequences (Binary, rhythmic pulses)

AI-Driven Pattern Recognition (Detecting structures we can’t perceive)

Non-Verbal Gestural Language (Using movement or mimicry to build shared meaning)

Perhaps our first conversation with extraterrestrials won’t be words at all—but patterns, movement, and sound.

Universal Grammar May Not Be So ‘Universal’ After All

Universal Grammar (UG), proposed by Noam Chomsky, suggests that all human languages share a built-in mental framework for structure and rules. However, in a first-contact scenario, this assumption may break down because:

It assumes all language is built on human cognition, which may not apply to non-humans.

It emphasizes syntax and structure, but alien communication might not have a structured “grammar” at all.

Instead, functional and cognitive linguistics (which focus on how meaning arises from context and use) may be more flexible when dealing with non-human or alien communication. These models look at language as a tool shaped by environment and social needs, which could help us interpret how an alien species might communicate differently from us.

Final Thought: If first contact happens, it won’t be about words—it'‘ll be about patterns, signals, and meaning. And if we can’t recognize that, we may miss the message entirely.

Coming Next

In Part 3 of Whale's Song, we’ll explore how scientists are actively decoding non-human languages—and what that means for our search for extraterrestrial intelligence.

If AI cracks the meaning of a whale’s song, would we finally consider it “language”?

And if AI tells us it has found a message—not from Earth, but from the stars—what happens next?

I am loving this topic. I am on a mission to read all your Whale Song posts.

I don’t know if you’ve read Sara Imari Walker’s “Life as No One Knows it” but as I read this piece of yours a lot of the ideas in it reminded me of that book. I think she has some lectures and such that might introduce her ideas and work more quickly than the book.

It’s not about communication per se, but is related.