What Poetry and Math Share—Constraint, Record, and the Refusal of Closure

Why do some texts remain usable across centuries while others age quickly?

Poems often explain too much to last as records.

Durability is not about beauty or insight; it’s about structural constraint.

Enter mathematics.

Poetry that endures does so for the same reason mathematics endure—they preserve relations by excluding interpretations.

Interpretations bring conclusion—finality.

Poets like Matsuo Bashō defy finality.

What We Mean by a “Record”

Record is not narrative. Narrative speaks of interpretation. Record speaks of evidence.

A record preserves initial conditions, a change, or perturbation, and an observable consequence.

It does not resolve meaning.

Records last when they report observations. Interpretations come and go.

So when a poem explains too much, which it has every right to do, it’s destined not to stand the test of time as a record.

The hallmarks of mathematics—proofs, datasets, and models—also function as records. They record relationships, not experiences. And that other part of math—explanations or solutions—is only found downstream, not inside the record itself.

Not all math resembles poetry.

Not all poetry functions as record.

But that which does … transcends time.

The Bashō Haiku as Minimal Record

The haiku attributed to Matsuo Bashō is often translated as:

An old pond—

a frog jumps in,

sound of water.

It is among the most famous poems in the world, which has made it dangerously easy to stop seeing. But if we approach it not as literature, and not even as Zen teaching, but as a record—something closer to data than decoration—it begins to behave differently.

What is preserved here is not the frog, nor the pond, nor even the poet. What is preserved is an event: a moment of interruption registered through sound. Stillness, motion, consequence. No motive is assigned. No meaning is offered. The poem does not tell us what the sound signifies. It tells us only that it occurred—and that it mattered enough to keep.

This restraint is the poem’s power.

Before there were instruments capable of measuring pressure waves or quantifying time at fine scales, humans still noticed change. We noticed when silence broke. We noticed when something altered the field of attention. Bashō’s haiku does not analyze that noticing; it encodes it. In doing so, it performs a function we now associate with data: it selects a signal from noise, compresses it, and stores it in a durable form.

The poem is extraordinarily economical. It excludes weather, emotion, explanation, and aftermath. This is not because those things were absent, but because including them would weaken the record. What remains is a minimal structure: background condition, perturbation, observable effect. In modern terms, the poem preserves variables while refusing interpretation.

That refusal matters.

Many texts fail as long-lived artifacts because they explain too much. They close meaning prematurely, binding observation to the worldview of the moment. Bashō’s haiku does the opposite. It leaves the event unresolved. Because of that, it can be reread across centuries—by poets, by philosophers, by neuroscientists interested in attention, by physicists thinking about signal emergence. The poem has not changed; the instruments have.

Even the physical form in which the poem survives reinforces this function. The haiku exists not as a single, fixed manuscript, but in multiple tanzaku—poem slips written in brush and ink, some attributed to Bashō’s own hand. Each is an instantiation rather than a definitive original. The poem’s durability does not depend on uniqueness, but on structure. It is repeatable without degradation.

This is where poetry and data resonate most strongly. Both rely on constraint. Both survive by exclusion. Both aim to preserve something real without exhausting it. And both depend on a reader—or analyst—who is willing to encounter what remains without rushing to explain it away.

The haiku does not end wonder when inference begins. It ensures that inference can begin at all.

In a culture that often treats explanation as closure, Bashō’s poem reminds us that the most durable records are those that stop just short of certainty. The sound of water is enough. The rest is left to time.

Bashō has given us an observation, a record. No explanation.

Let’s now turn to how this compares with other poetry—poetry that does not function as record.

“The most powerful records stop just short of meaning.”

First Contrast: Emotion as Closure (William Wordsworth)

I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud (Daffodils) is a lyric poem by William Wordsworth that was one of the defining works of English Romanticism. Many familiar with Wordsworth define him as a ‘poet of perception and nature.’

The full poem can be found here: I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud. If you read the poem, you will see that Wordsworth indeed observes, but he extends beyond citing what he sees by also promoting an emotional valuation and reflective payoff. It’s one of the beauties of the poem, but it’s not a record.

Bashō records a condition, a disturbance, and a perceptible outcome.

Wordsworth records a condition as well, but he folds it into his inner life. The daffodils do not merely occur. They console.

This, of course, is not a weakness as poetry—but it does limit its durability as a data-like artifact. It binds the event to a specific psychological outcome. The reader is told how the observation should function, and the moment becomes no longer open-ended; it’s resolved.

Not wrong, just not record.

Bashō never tells us what the sound of the frog jumping into the water does to him. That omission is the entire point.

Second Contrast: Concept as Closure (Wallace Stevens)

In The Snow Man, Stevens is much closer to Bashō in temperament than Wordsworth. Spare. Observant. Intellectually disciplined.

At first glance, The Snow Man looks like a model poetic record: stripped imagery, winter landscape, refusal of sentimentality.

Alas, Stevens cannot resist epistemological instruction.

The poem explicitly teaches the reader how to perceive:

“One [must] have a mind of winter…”

The Snow Man breaks as a record when Stevens encodes not just the observation, but the theory of observation.

The poem includes its own interpretive framework, with perception conditional upon philosophical readiness. Thus, the record becomes inseparable from its explanation.

This makes the poem brilliant—but less portable across time and disciplines. It tells us how to see, not just what occurred.

Bashō, instead, assumes only attention; he does not specify the required mind.

Not Better but Structurally Different

Wordsworth’s I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud adds meaning and consolation, but fails as record by providing emotional closure, costing the reader openness.

Stevens’ The Snow Man provides philosophical rigor, but fails as record because of conceptual closure. It thus lacks reusability by the reader.

Through deliberate restraint, Bashō attains durability at the cost of authorial presence—and succeeds in creating lasting records.

Bashō is not better. He is structurally different.

That difference explains why his haiku behaves so well under rereading, translation, scientific analogy, and time.

This is where math and poetry truly meet.

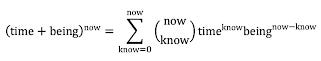

Constraint as a Shared Survival Strategy

In mathematics, elegance emerges from limitation. Proofs fail when they explain too much.

In poetry, durability emerges from what is withheld. The reader completes the system.

Both share compression, invariance, reusability, and resistance to premature certainty.

Explanation binds a record to its era.

Restraint allows re-instrumentation across time.

The most powerful records stop just short of meaning.

While poetry and mathematics share much, we must respect that poetry does not, cannot, replace science.

But it does preserve the conditions that make inquiry—scientific and otherwise—possible.

Closing: The Sound That Was Kept

Neither haiku nor Bashō end wonder.

Instead, they ensure wonder survives long enough for inference to begin.

In a culture obsessed with explanation, restraint is a radical act. It’s a difficult act.

But when we practice it in writing, when we don’t tell readers what to think, we are left with something real, intact, and unresolved … something more likely to endure.

I would have loved this essay as a class during my English major undergrad years. It was Zen to read and process. I needed it today!

This is such a fascinating essay. I relate to writing through feeling it. So, an intellectual breakdown of poetry, I cannot really feel it, so therefore, my natural inclination is to resist what you have said. But I think I really need to look at it more.