Why Invent a Language?

Essay One in a new series: Crafting the Whale's Tongue

What if you heard a signal you knew was a language, but you couldn’t even understand its alphabet?

Years ago, in Hawaii, I sat on a boat with a hydrophone and heard whale song. A deep moan. A call? A song? A message? It latched onto me and still echoes in my soul today.

The whales were speaking. I was sure. But what were they saying?

That mystery—knowing there was a language but not its alphabet—planted the seed. Why invent a language? Because without one, the voice of another remains locked away.

From Whales to Worlds

Hawaii was a long time ago—a yesterday.

Today, I find myself speaking on behalf of the Biet Lagos—an alien species at the heart of my work-in-progress, World Beyond the Song. They are not yet on stage in full, but their presence hums beneath the surface.

They are speaking, and I know what they are saying—because I built Threlraan, their language.

And so the question rises again: Why invent a language? Because if we don’t, we risk silence where connection should be.

Inventing a language is not an easy task. But it is deeply rewarding. To invent a language is to imagine how connection might sound beyond the limits of human speech. In sharing Threlraan, I’m not just inviting you to listen to the Biet Lagos. I’m inviting you to listen for the deeper song that threads through whales, through us, and perhaps through all life.

What’s in It for Me?

World Beyond the Song is, at its core, a story about connection and communication. That’s where the true answer lies: we invent languages to explore what it means to connect when ordinary words fall short.

And, perhaps, because I plan to be a whale in my next existence. Therefore, whales had to be in my story.

I’ve long felt uneasy about how our modern ways of “connecting”—especially online —often seem to isolate us more than they unite us. Whales, with their intricate communication, offered me a model. Long before I knew what SETI was, I imagined that learning to speak whale would be the perfect template for learning to speak alien.

Oddly enough, speculative fiction wasn’t my original path. I once thought my first novel would be historical fiction—the story of a 7th-century monk on the Isle of Eigg. History still tugs at me. And even there, language calls: ancient cuneiform, clay tablets, marks carved in the hope of bridging silence.

Whether with whales or monks or alien voices, the thread is the same: why invent a language? Because humanity has always sought ways to speak across the void.

What’s in It for You?

When I launched Wander Words, I began with Whale’s Song—a series exploring how cetacean communication can inspire alien language in fiction. (You can find the introduction here → Whale’s Song: Intro.)

But I knew the old tropes—the “universal translator,” or a generic alien tongue that just sounds strange—wouldn’t be enough. The Biet Lagos deserved better. We deserve better.

If a people have no tongue of their own, they cannot be fully alive—not on the page, and not in the imagination.

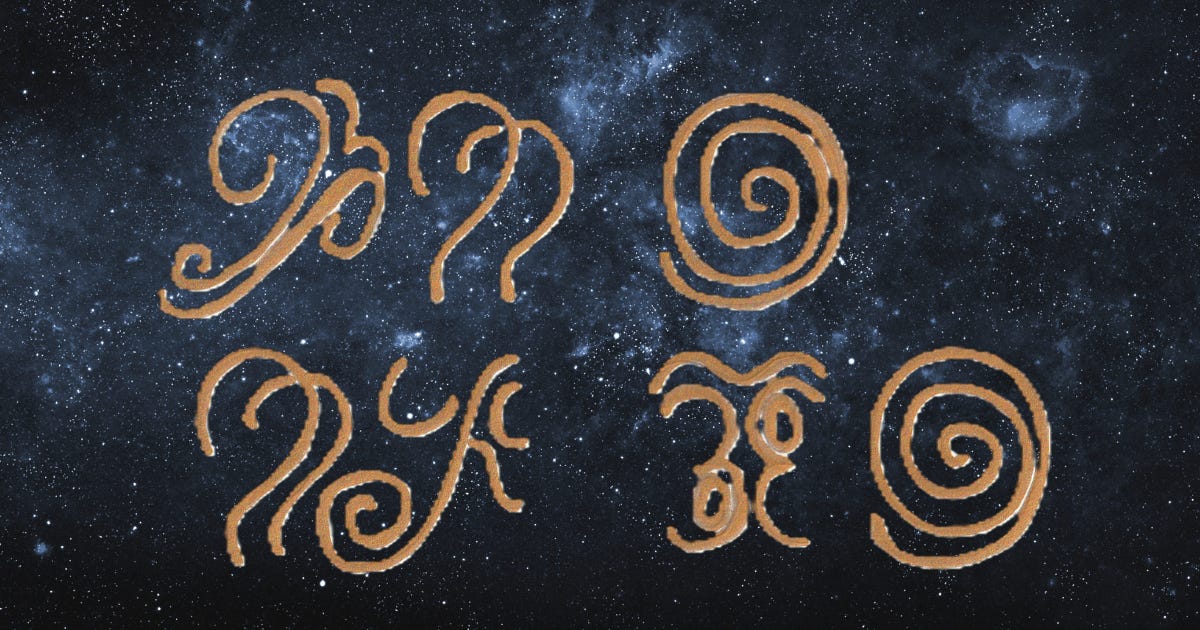

Thus, Threlraan emerged.

From the Depths Did Threlraan Emerge

Let me tell you about Mycte (pronounced my-cete), the homeworld of the Biet Lagos. Once an icy shell planet with subsurface oceans, it evolved into a largely water world, dotted with archipelagos and one unstable supercontinent.

The Biet Lagos can live on land and endure in space for short periods, but their lives are shaped by the ocean. Land is sacred; space is exploratory.

Their communication reflects this. It is multimodal—bioluminescent pulses, movement, a visceral hum akin to song.

Song is, perhaps, the universal medium. It transcends intellect and strikes the primal chord of vibration, rhythm, resonance. And maybe that is the truest answer to our question: we invent languages because life itself speaks in song, and it is only right that we learn to listen.

Bioluminescence gave their earliest words visibility in the dark oceans. Pulses added rhythm, a way of feeling meaning. Hums and guttural clicks brought sound into the conversation. When the oceans rose to the surface, the Biet Lagos expanded their voices to space itself—where threads weave into songs. (Ask Issi.)

The Real Challenge

Enter Jayla, my protagonist—a brilliant xenolinguist, hungry for first contact.

One of the hardest parts of developing Threlraan was designing a language she would truly struggle to decode. It could not be too human, nor utterly alien. It had to feel daunting, yet possible.

So I entertained strange options:

What if rhythm defined grammar?

What if silence spoke volumes—a noun, an adjective, an entire phrase?

What if colors carried meaning through a kind of synesthesia?

Jayla stared at the pulse pattern: three beats, pause, two beats, long shimmer. It wasn’t random. But what kind of mind would choose this rhythm?

As the writer, I know more than Jayla does. But part of the craft is deciding how much she can glimpse—and how much must remain hidden, for both her and for you.

That is the challenge—and the joy—of inventing a language.

Closing Reflection

Have you ever heard something—a chant, a birdsong, a lullaby—and known it meant more than sound?

Threlraan, the language of the Biet Lagos, began not as words on a page, but as a shimmer in the dark. For me, inventing it has never been about vocabulary lists. It’s about asking one essential question:

How do you connect with something that doesn’t even share your senses?

It's nice how you explain language invention as an act of empathy, giving voice to the other to avoid silence where connection should be. Thank you for sharing.

I also have a personal question I wanted to ask, I left it inbox, when you have time please check it out.

As a novice sci-fi writer this post intrigued me. I adore the intricate world-building behind the language of the Biet Lagos but, more importantly, the multimodal aspect of it. It prompted memories of the species in Arrival.

I love the way you have used supplementary content to enrich your world and to draw me to reading your work, which I shall be doing. I am taking notes on what to share about my own work without revealing too much to potential readers.

Thank you for sharing

Gary