To understand creativity as movement rather than identity, it helps to watch a life that was lived that way—deliberately, repeatedly, and without apology.

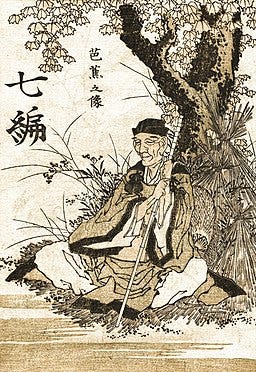

Matsuo Bashō did not become a writer by settling into a single role. He became one by moving—physically, spiritually, and creatively—through different states of attention over time.

Bashō’s practice begins, again and again, with gathering. He read deeply in classical Chinese and Japanese poetry. He observed landscapes, weather, customs, small human moments. His travel journals are records of attention more than events. The world entered him slowly, through notice.

From there, Bashō often lingered in incubation. His journeys were not undertaken to produce poems on schedule. He walked long distances, endured discomfort, and allowed experience to work on him without immediate demand. Many poems arrived only after extended silence. Readiness mattered more than output.

When articulation came, it was exact. Bashō’s haiku are brief, but they are not rushed. Each poem feels released rather than produced—language arriving when it could no longer be held inside. What appears effortless is usually the end of a long internal process.

Revision and teaching placed Bashō in the shaping state. He refined poems, guided students, and insisted on discipline within form. For him, structure was not constraint but vessel. Clarity was not simplification; it was care.

As a teacher and leader of a poetic circle, Bashō also lived in the state of offering. Poetry was shared, exchanged, responded to. Writing was not a private performance but a communal act. Meaning expanded through relationship.

And then—repeatedly—Bashō withdrew. He left positions of comfort and status. He chose solitude. These moments of guardianship are sometimes romanticized, sometimes misunderstood. They were neither escape nor failure. They were acts of preservation—of attention, of integrity, of life.

Seen whole, Bashō’s creative life does not trace a straight line. It cycles.

He gathered.

He waited.

He spoke.

He refined.

He offered.

He withdrew.

And then he began again.

What Bashō shows us is not how to write haiku, or how to live as a poet, but something more durable: that creative work is sustained not by consistency of identity, but by willingness to move—to recognize when one state has done its work and another is asking to take its place.

There is no single posture that made Bashō Bashō.

There was only attention, and motion, and return.

A closing reflection (optional)

As you think back over the past few days—

the archetypes, the pairings, the questions—

consider this quietly:

Where have you been lingering?

Where might movement be waiting?

You don’t need to answer.

Noticing is enough.

Some readers may want to sit here, and that’s enough.

Others may be curious how these same creative states appear in a very different life, language, and century.If you’d like to continue, you can read another “Author in Motion” reflection—this time with Virginia Woolf.

A final note

This series does not ask you to decide who you are as a writer—or as a creative person.

It asks something simpler, and harder:

Where are you, right now?

That question can be returned to.

Again and again.

I love Basho’s work and writings. As you say, so much is about attention. I relate deeply to his ways. Thank you for sharing this JL.