Writing the Light

Crafting the Whale's Tongue series - Essay Five

Writing the Light

Crafting the Whale’s Tongue is a series describing my creation of an alien language for World Beyond the Song.

To catch up or review the preceding essays, you can find those works here:

Now, we explore the motivations and trends that led to the development of writing systems.

The Urge to Record

“I write only because / There is a voice within me / That will not be still.”

— Sylvia Plath

Speech vanishes the moment it’s spoken. To endure, words need marks. Humans solved this by inventing writing—pressing sound into clay, carving meaning into stone. Cuneiform, one of the earliest systems, shows how sound became sign, and sign became record.

The Biet Lagos faced the same urge. If their words are law, as we explored in the last essay, how can law survive beyond ritual performance? Their answer was to fix pulses and rhythms into something enduring: glyphs of light.

This essay in the Crafting the Whale’s Tongue series explores how sound becomes glyph, and glyph becomes meaning—drawing from cuneiform but moving toward Threlraan. Early sketches reveal how their pulses echo into shapes, and how Jayla, my xenolinguist protagonist, must learn to decode these luminous inscriptions.

From Sound to Glyph

Recall that the Biet Lagos heavily rely on bioluminescent light pulses, rhythm, and gestures to communicate (see Physiology Shapes Speech).

Writing was never about contracts; it was about echoes that endure beyond the body.

It’s about echoes that endure beyond the body.

Without a form of writing, the echoes might someday be lost. So over time, a written language evolved, where script became a fossilized pulse—a way to hold a tone or a law in stillness when the voices that sang were gone.

For the Biet Lagos, script became a fossilized pulse —

a way to hold a tone or law in stillness.

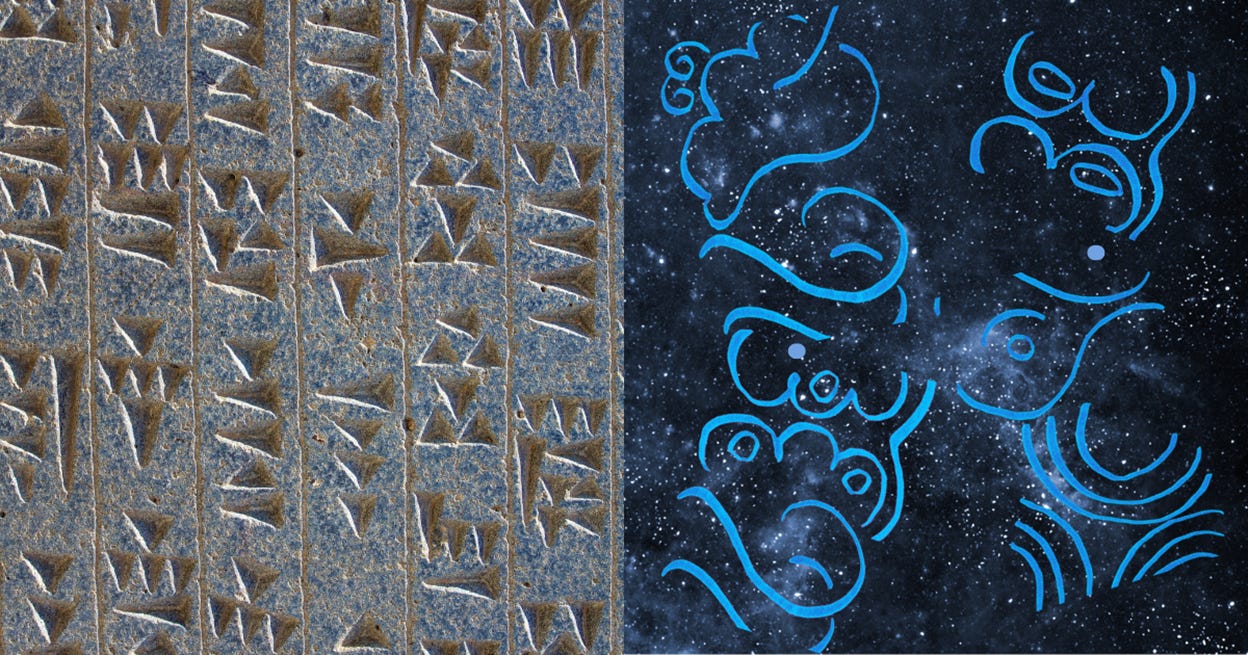

For the Biet Lagos, rhythms of light, pulses, and dance emerged naturally as abstracted patterns. By way of example, we can examine how humans abstracted sounds into wedge-shaped marks, i.e., cuneiform.

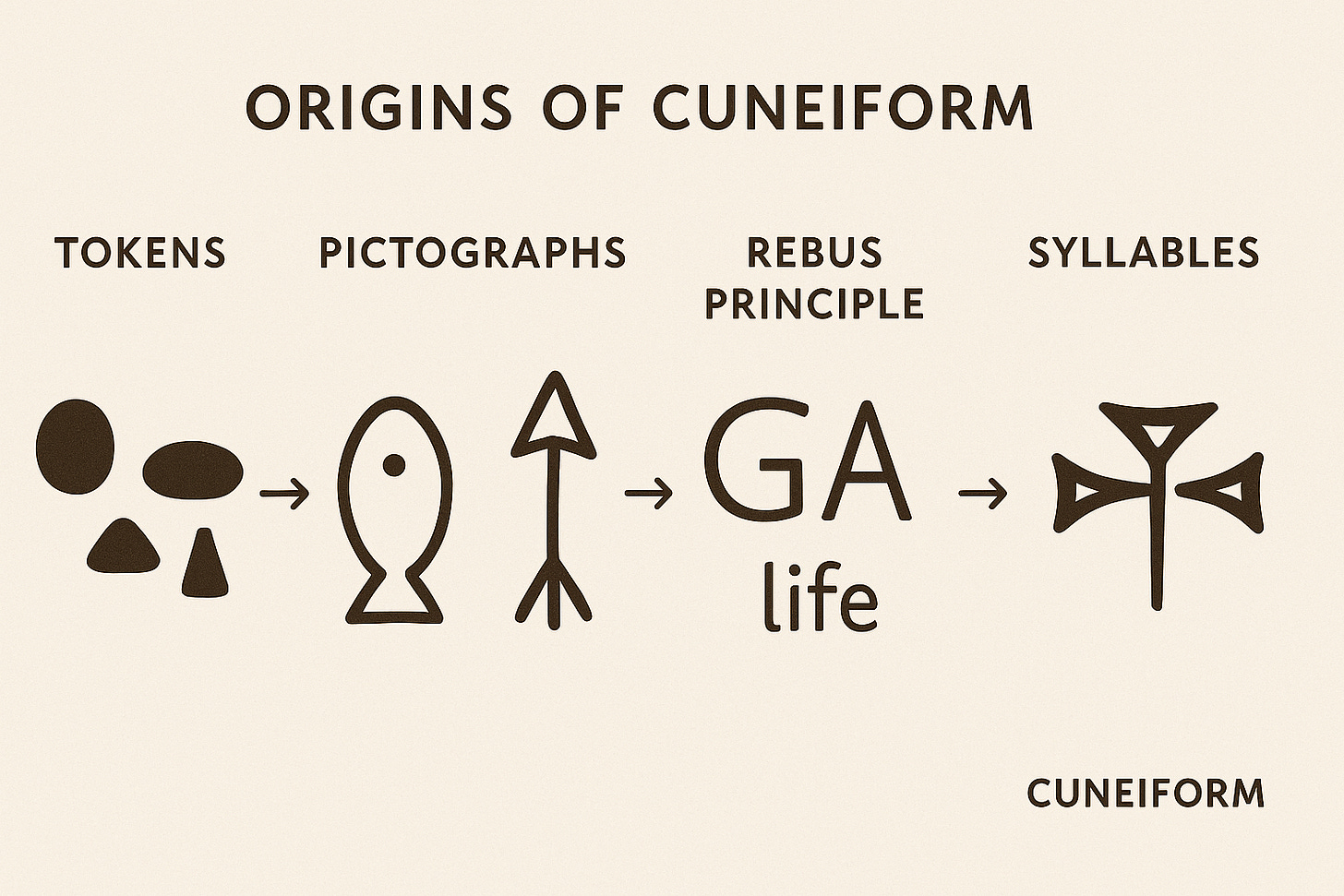

It started with clay tokens, ca. 8000-3500 BCE. In Mesopotamia, people first used small clay tokens to represent goods—one token for a sheep, another for a jar of oil, and so on. Over time, instead of carrying bags of tokens, scribes began pressing the tokens into clay tablets to record quantities.

Around 3200 BCE, scribes began drawing simplified pictures of objects directly on clay tablets. These early pictographs represented things, but not spoken language. It wasn’t until ‘rebus’ came along that pictures came to represent sounds.

For example, if the Sumerian word for “arrow” sounded like part of the word for “life,” the arrow sign could be used to write “life.” The rebus principle revolutionized writing. This same principle underlies Threlraan: a pulse that once meant only ‘light’ might later carry the sound of a syllable.

Once sound values entered the system, scribes combined them to spell out names, abstract ideas, and grammatical markers. Cuneiform signs began representing syllables (ba, ki, mu) rather than just whole words.

Over time, curved pictographs were simplified into angular wedge patterns made by impressions from a reed stylus pressed into soft clay. Thus, cuneiform was born. “Cuneiform” is Latin for ‘wedge-shaped.’ Sensible.

In fact, it made so much sense for developing a writing system, the Biet Lagos may have copied the progression … oops …getting too close to spoilers. Just know it’s not coincidental that Threlraan, the written form of the Biet Lagos language, follows the logic of cuneiform and Old Akkadian.

Echoes of the Pulse

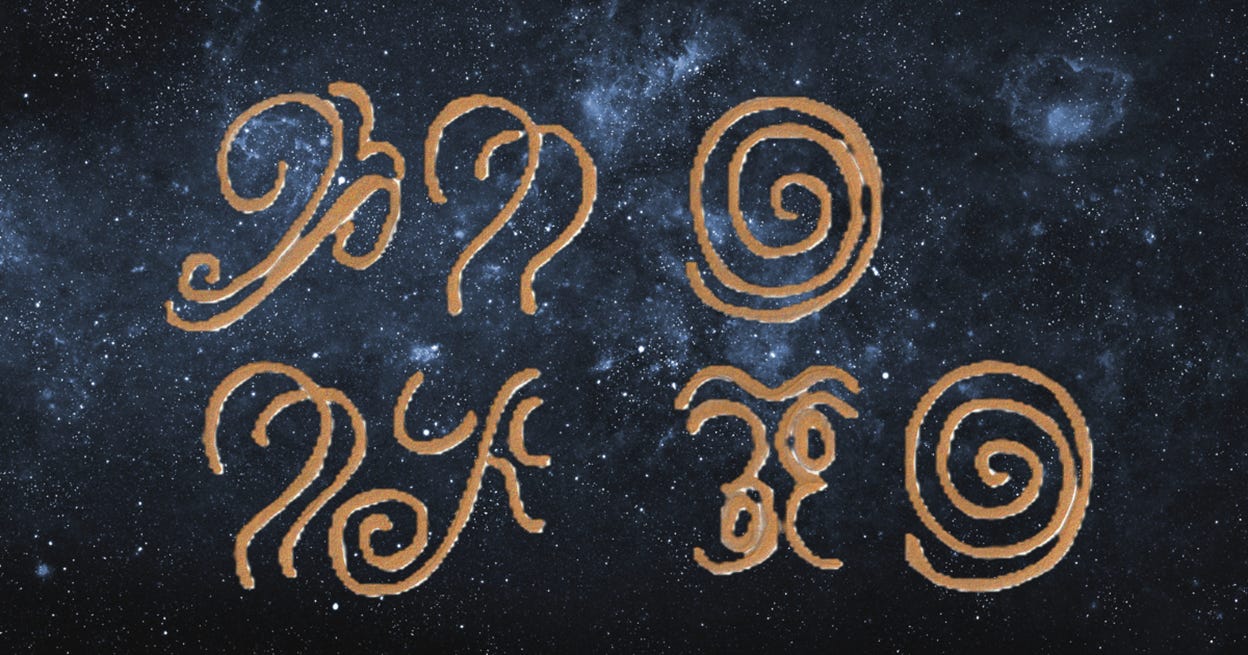

The development of Threlraan mirrored a familiar path: starting with fundamental “tokens” like pulses and rhythmic clicks, progressing to patterns rather than pictographs, and eventually employing a rebus-type principle to create glyphs akin to cuneiform syllables.

These Threlraan glyphs, far from arbitrary, are more intricate than they seem. They were crafted to reflect the shape and sensation of bioluminescent pulses.

Over time, these glyphs incorporated not just the rhythm of the pulses, but also the patterns of clicks and the nuances of gestures.

Threls are the basic strokes; glyphs combine threls into syllables; script is the full writing system.

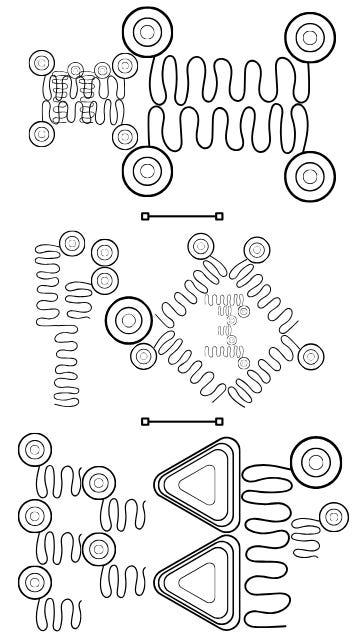

What once was this:

has evolved into this:

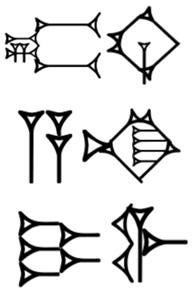

Each of the above Threlraan glyphs align with the logic of Old Akkadian cuneiform syllables below:

You may see the correlations between all three versions, but Jayla, our favorite xenolinguist, will not have the advantage of such a side-by-side comparison. Likewise, you, the reader, are unable to hear the audible clicks that will accompany the message to be decoded.

The second image, modern Threlraan, if you will, as an image alone contains the patterns that align with, not only words, but sounds. And not only sounds and words, but mood and intention.

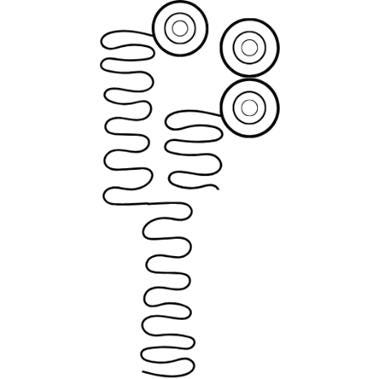

Let’s look at a single Threlraan glyph to see what it truly contains.

How a Single Threlraan Glyph Evolves

A threl is not just seen. It is heard, felt, and seen in color simultaneously.

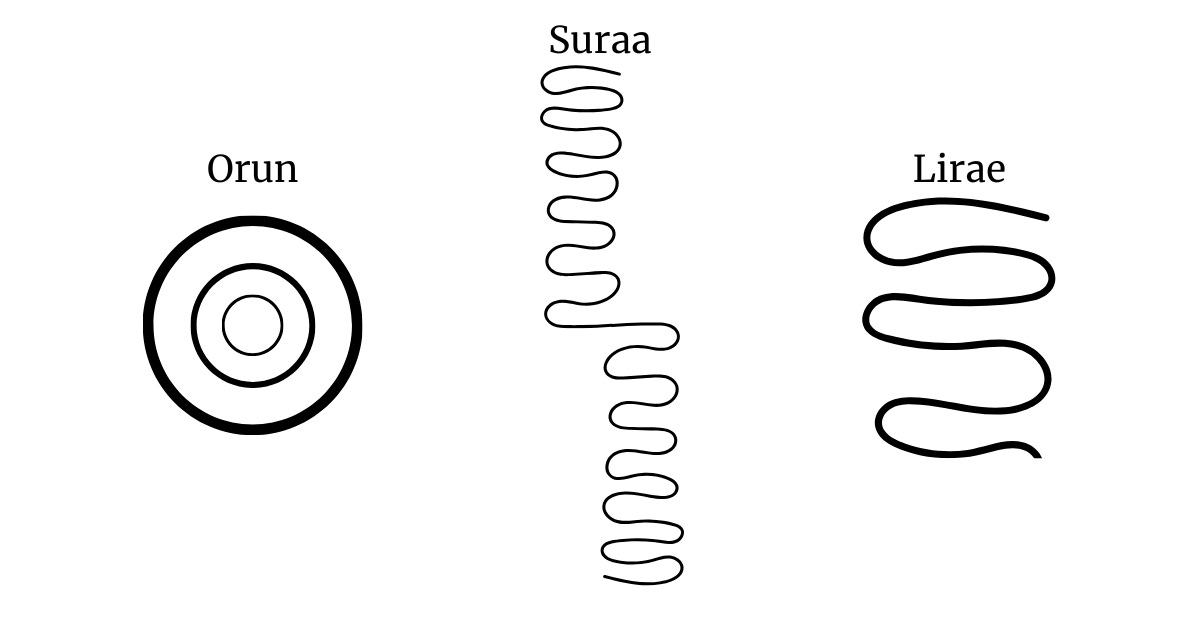

The glyph above represents the syllable ‘a’ in Threlraan. All threls are made from six base components. In the ‘a’ syllable above we find three constituents: orun, suraa, and lirae. (Note the images are not matching in scale).

Beyond the basic shapes, each threl differs in its base rhythm, semantic field, and color. Further, these three features change based on orientation (e.g., vertical, horizontal, diagonal, etc.), insertion or stacking with other threls, and mood or intention.

Here is an example of a codex entry describing a threl component:

Orun

Name: Threl Orun (“echo / resonance”)

Shape Essence: Center + ripple outward

Base Rhythm: Long hum → soft fade → hum (like rippling gong)

Semantic Field: Origin, presence, amplification, “I am”

Orientation Effects:

Upright (default) = stable resonance

Tilted = unstable / questioning resonance

Insertion/Stacking:

If another threl is placed inside → meaning shifts to “carried by origin” (e.g., Orun + Veyr = “warning from the core”).

If another threl is stacked adjacent to it, overall resonance is deepened

Color Layer:

Blue = depth, sincerity

Red = alarm, danger

Violet = sacred memory

This codex entry should show how much information can be packed into even the tiniest part of something. Decoding a Threlraan “word,” or even just a single “threl,” would be a real challenge.

Jayla, our brilliant xenolinguist, faces a significant challenge: she knows less about Threlraan fundamentals than we do. Regardless of the outcome, she’ll need considerable determination to decipher the Biet Lagos’s message.

Even a single misinterpretation—the color of a light pulse, for instance, or threl orientation—could mean the difference between success and utter failure.

Like Earth’s writing systems, which evolved from pictures to wedges and finally phonetic symbols, the Biet Lagos’s Threlraan also developed over time.

However, as synesthetes with an aquatic nature, they perceive and communicate in ways we might not anticipate.

To inscribe a glyph is to fix a moment of law, a fragment of song, into something that can endure when voices fall silent.

Writing vs. Weaving

We’ll explore this synesthetic multimodality more fully in the next essay—how meaning transforms when sound, light, and gesture converge. Suffice it to say that Threlraan is anchored in multi-sensory cues and no single channel is primary.

A threl is not just seen as a line or shape. It is heard as a pulse, felt as vibration, and seen as color shimmer simultaneously.

When Jayla tries to decode the alien message, she won't be able to just analyze the shapes, sounds, or colors of each symbol on their own. To truly understand, she'll need to experience the message the way the Biet Lagos do. This means she'll have to stop focusing on sight and sound as separate things and learn to perceive them together.

Biet Lagos writing bridges oral performance and fixed record in ways we haven’t yet imagined. Should we expect any less from an advanced alien species?

Closing Reflection — When Light Becomes Memory

Threlraan is more than a constructed language—it is a weave of pulse, rhythm, and memory. To inscribe a glyph is to fix a moment of law, a fragment of song, into something that can endure when voices fall silent. For the Biet Lagos, writing the light is not about recording history—it’s about binding truth to the fabric of the cosmos.

Next time, we’ll follow that fabric into motion—how meaning shifts when sound, light, and gesture converge in full multimodality.

Have you ever invented a language?

What do you imagine the most fun to be in inventing a language?

How about the most challenging?

What would you write in Threlraan if you could?

Another fascinating essay! I love how you're bringing us into the depths of this, exploring how this language can't really be translated the way most of us think of it. For example, if I was translating something in Spanish I'd know "casa" is "house" and "queso" is "cheese" but Threlraan doesn't seem to lend itself toward word-to-word interpretation. It's almost as if you have to feel the meaning and then totally recompose it in another language. Really cool stuff!