THE STAR ARCHIVE: HOW POETRY SAVED THE SKY

Introduction to a New Series

last updated: 11 December 2025

Before astronomy was a science, it was a literary art.

The oldest surviving poems on Earth do not describe flowers or love or war. They look upward.

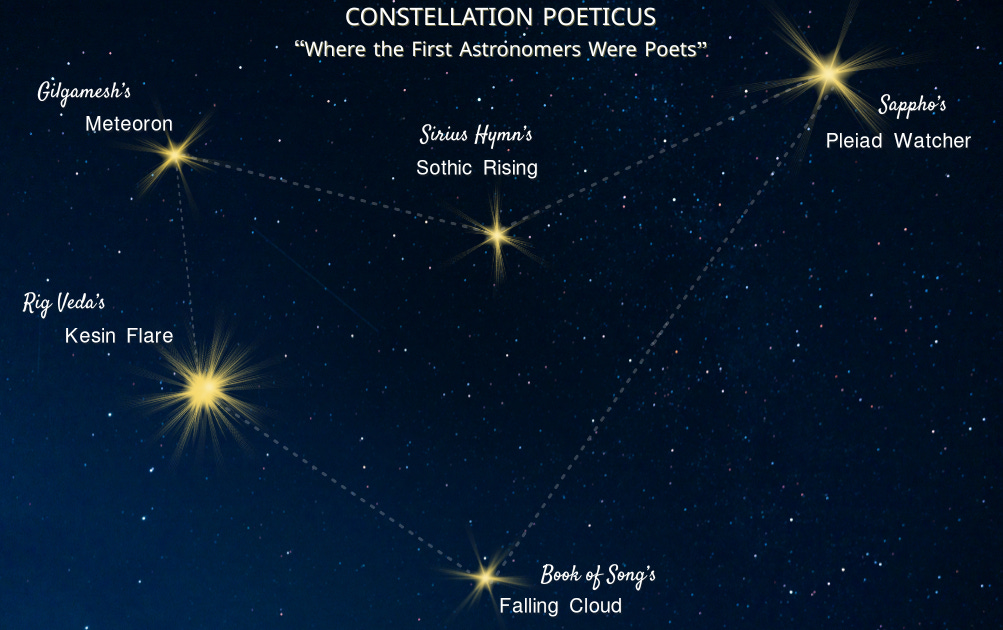

In Mesopotamia, over four thousand years ago, the Epic of Gilgamesh begins with a dream of a star falling from the sky and striking the land.

In India’s Rig Veda, a blazing being crosses the heavens “burning like the sun,” now read as a probable fireball meteor.

On the island of Lesbos, Sappho marks the hour by the setting of the moon and the Pleiades—a moment astronomers can now date to a specific season around 570 BCE.

In China’s Book of Songs, stars “gather and fall in streaks,” a poetic description that matches what we now call a meteor shower.

And in Egypt, a hymn to Sirius—the goddess Sopdet—marks the star’s annual rising, used to predict the Nile flood and structure the agricultural year.

These are not astronomical documents.

And yet, every one of them preserves a real celestial event.

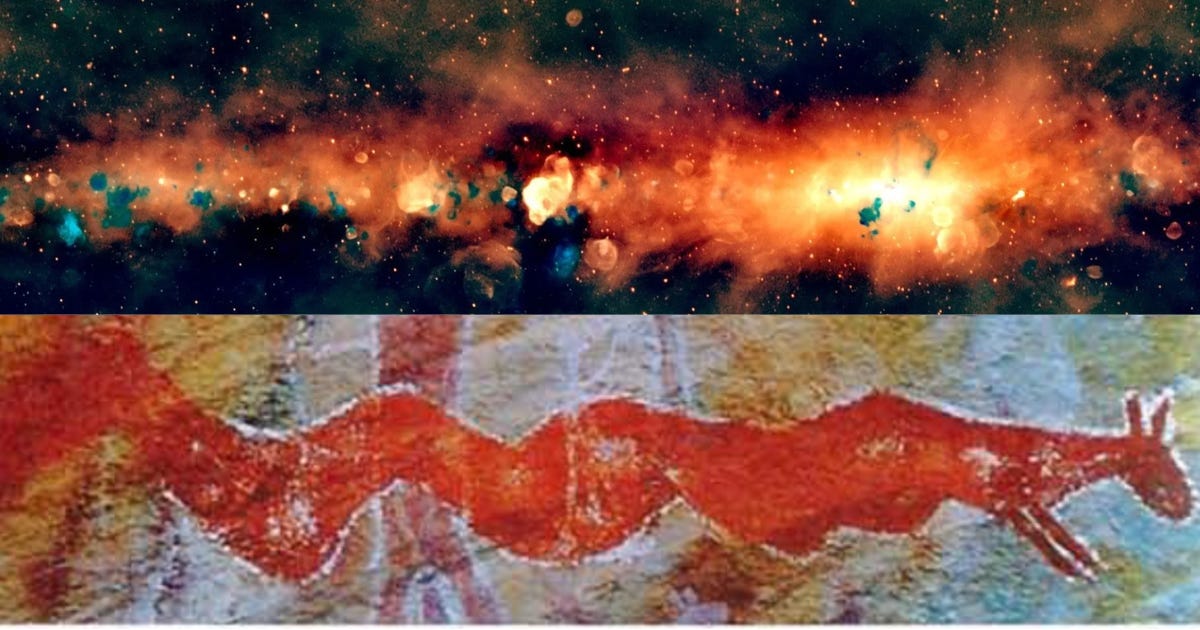

Something in the sky looks like something in the painting.

Sometimes the language is literal; sometimes mythic. Sometimes the poet is trying to measure time; sometimes they’re simply trying to survive awe. But the pattern is unmistakable.

Human beings watched the sky, and they stored what they saw in poetry.

We have been doing that longer than we have kept archives, longer than we have kept clocks, longer, perhaps, than we have kept cities.

What makes this astonishing is not simply the age of these texts. It’s that modern astronomers can still read them.

The Rig Veda’s blazing god matches the physics of a bolide—an exceptionally bright meteor. Sappho’s heartbreak contains the timing data of a stellar setting. The Gilgamesh star falls with the violence of an impactor.

We now have the vocabulary those poets didn’t—supernovae, comets, light curves, spectral classes—but the poems have outlived every instrument used to describe the same night sky.

This essay series is an inquiry into that phenomenon.

Not just astronomical history. Not merely literary curiosity. A deeper question.

Why did we tell the sky to poetry, and what made us stop?

And why does it feel like we are beginning to do it again?

Because we are.

There is a resurgence now—science-fiction poetry, cosmic elegy, astrophysical lyric.

Modern poets write about dark matter and exoplanets the way ancient ones wrote about comets and gods. Some of our poems are being launched into space again—as if, across centuries, we have looped back to something essential.

Maybe poetry is not the opposite of science.

Maybe it is the oldest form of it.

Five essays follow. Each looks at a different moment when the heavens broke through metaphor, and verse became recordkeeping:

1. The First Astronomers Were Poets

2. Dragons in the Sky: When Celestial Events Become Myth

3. Pictographs and the Poetry That Doesn’t Use Words

4. The Crab’s Claim: Evidence After Attention

5. Where the Telescope Meets the Lyric: Science-Fiction Poetry Now

I’m not hoping to prove a theory. I’m hoping to open a door.

To step into the lineage.

To stand where our earliest writers stood—looking up, a little frightened, a little in love—and whisper back across time:

We saw it too.

We are still watching.

We are still writing it down.

A star explodes once.

A poem can remember it forever.

Next week, the stars unfold with Essay 1: The First Astronomers Were Poets.

Oh, this is beautiful. I'm looking forward to the essays! You've conjured memories of sitting on the beach with Anna, gazing up at the stars, recognizing that the light we're seeing left its origin millions of years ago. I think, no matter how much science and understanding we gain, the night sky will always invoke wonder. It seems like something fundamentally human.